CS 6200 Introduction to Operating Systems

What is an Operating System

Shop Manager Metaphor

A shop manager:

- Directs operational resources: use of employee time, parts, tools

- Enforces working policies: fairness, safety, cleanup

- Mitigates difficulty of complex tasks: simplifies operation, optimizes performance

An operating system:

- Directs operational resources: use of CPU, memory, peripheral devices

- Enforces working policies: fair resource access, limits to resource usage

- Mitigates difficulty of complex tasks: abstract hardware details (system calls)

Attempt do define an operating system

Hardwares (CPU, Memory, GPU, Storage, Network Card) are used by multiple applications. The operating system sits in between the underlying hardwares and the applications. It:

- hides hardware complexity

- manages resource (schedule tasks on CPU, manages memory usage)

- provide isolation and protection (so application do not interfere with each other)

Operating System Definition

An operating system is a layer of systems software that:

- directly has privileged access to the underlying hardware

- hides the hardware complexity (abstraction)

- manages hardware on behalf of one or more applications according to some predefined policies (arbitration)

- ensures that applications are isolated and protected from one another

Operating Systems Examples

Desktop:

- Microsoft Windows

- Unix-based

- Mac OSX (BSD)

- Linux (Ubuntu, Centos, Fedora)

Embedded:

- Android (Linux)

- iOS

- Symbian

Mainframe

Operating System Elements

- Abstractions:

- application: process, thread

- hardware: file, socket, memory page

- Mechanisms:

- application: create, schedule

- hardware: open, write, allocate

- Policies (how mechanisms will be used):

- least-recently used (LRU)

- earliest deadline first (EDF)

Memory management example

- Abstractions: memory page

- Mechanism: allocate, map to a process

- Policies: least recently used (least recently used memory page will be moved to disk, a.k.a swap)

Design Principles

Separation of mechanism and policy

Implement flexible mechanisms to support many policies, e.g. LRU, LFU, random

Optimize for common case

- Where will the OS be used?

- What will user want to execute on that machine?

- What are the workload requirements?

User/Kernel Protection Boundary

- Kernel level: OS Kernel, privileged mode, direct hardware access

- User level: unprivileged mode, applications

user-kernel switch is supported by hardware:

- trap instructions

- system call: open (file), send (socket), mmap (memory)

- signals

System Call Flowchart

Flow of synchronous mode: wait until the sys call completes

- (user process) User process executing

- (user process) Call system call

- (kernel) Trap

- (kernel) Execute system call

- (kernel) Return

- (user process) Return from system call

To make a system call an application must:

- write arguments

- save relevant data at well-defined location

- make system call

Crossing the User/Kernel Protection Boundary

User/Kernel Transitions

- hardware supported: e.g. traps on illegal instructions or memory accesses requiring special privilege

- involves a number of instructions: e.g. 50-100ns on a 2Ghz machine running linux

- switches locality: affects hardware cache!

Note on cache

Because context switches will swap the data/addresses currently in cache, the performance of applications can benefit or suffer based on how a context switch changes what is in cache at the time they are accessing it.

A cache would be considered hot if an application is accessing the cache when it contains the data/addresses it needs.

Likewise, a cache would be considered cold if an application is accessing the cache when it does not contain the data/addresses it needs – forcing it to retrieve data/addresses from main memory.

Basic OS Services

- Scheduler: access to CPU

- Memory manager

- Block device driver: e.g. disk

- File system

Windows vs Unix

- Process Control:

- Windows: CreateProcess, ExitProcess, WaitForSingleObject

- Unix: fork, exit, wait

- File Manipulation

- Windows: CreateFile, ReadFile, WriteFile, CloseHandle

- Unix: open, read, write, close

- Device Manipulation

- Windows: SetConsoleMode, ReadConsole, WriteConsole

- Unix: ioctl, read, write

- Information Maintenance

- Windows: GetCurrentProcessID, SetTime, Sleep

- Unix: getpid, alarm, sleep

- Communication

- Windows: CreatePipe, CreateFileMapping, MapViewofFile

- Unix: pipe, shmget, mmap

- Protection

- Windows: SetFileSecurity, InitializeSecurityDescriptor, SetSecurityDescriptorGroup

- Unix: chmod, umask, chown

Monolithic OS

Historically, OS had a monolithic design. Every possible service any application can require or hardware will make are already included.

- + everything included

- + inlining, compile-time optimization

- - customization, portability, manageability

- - memory footprint

- - performance

Modular OS

e.g. Linux

OS specifies interface for any module to be included in the OS. Modules can be installed dynamically.

- + maintainability

- + smaller footprint

- + less resource needs

- - indirection can impact performance

- - maintenance can still be an issue

Microkernel

Only require the most basic primitives at OS level. File system, disk driver, etc will run at unprivileged application level.

- + size

- + verifiability

- - portability

- - complexity of software development

- - cost of user/kernel crossing (more frequent)

Processes and Process Management

Simple Process Definition:

- Instance of an executing program

- Synonymous with “task” or “job”

Toy Shop Metaphor

An order of toys:

- state of execution: completed toys, waiting to be built

- parts and temporary holding area: plastic pieces, containers

- may require special hardware: sewing machine, glue gun

A process:

- state of execution: program counter, stack

- parts and temporary holding area: data, register state occupies state in memory

- may require special hardware: I/O devices

What is a process

OS manages hardware on behalf of applications. Applications are programs on disk, flash memory, etc. They are static entities. Once an application is loaded, it becomes an active entity and is called a process. Process represents the execution state of an active entity.

What does a process look like

Process encapsulate all states from an application, e.g. text, data, heap, stack. Every state has to be uniquely identified by its address. Address is defined as a range of address from $V_0$ to $V_\text{max}$.

Types of state:

- text and data: static state when process first loads

- heap: dynamically created during execution

- stack: grows and shrinks (LIFO queue)

What have been said above regarding the encapsulation can be called the address space. It is the “in memory” representation of a process. We call $V_0$ to $V_\text{max}$ used by the process virtual addresses, in contrast with physical addresses which correspond to locations in physical memory (e.g. DRAM). A Page table created by the OS maintains a mapping of virtual to physical addresses.

32bits: Virtual address space up to 4GB.

Some times applications can share the same physical addresses, and additional states will be swapped in and out of the disk.

How does the OS know what a process is doing

OS has to have idea of what a process is doing, so it can stop and restart the process at the same point.

- Program Counter: where in the instruction sequence the current is with

- CPU register: maintains program counter while the process is runner

- Stack pointer: where the top of the stack is. It’s important because stack is LIFO.

What is a Process Control Block (PCB)

A data structure that the operating system maintains for every one of the processes that it manages.

- process state, process number, program counter, registers, memory limits, list of open files, priority, signal mask, CPU scheduling info

- PCB created when process is created

- Certain fields are updated when process state changes

- Other fields change too frequently (e.g. registers)

What is a context switch

A context switch is the mechanism used by the operating system to switch the CPU from the context of one process to the context of another.

They are expensive:

- direct costs: number of cycles for load and store instructions

- indirect costs: cold cache! cache misses

Process Lifecycle

States of a process:

- New: when a process is created. OS will perform admission control, and create PCB.

- Ready: process is admitted, and ready to start executing. It isn’t actually running on the CPU and has to wait until the scheduler is ready to move it into a running state when it schedules it on the CPU.

- Running: ready state process is dispatched by the scheduler. It can be interuppted so that a context switch can be performed. This will move running process back into the ready state.

- Waiting: when a longer operation is initiated (e.g. reading data from disk, waiting for keyboard input), process enters waiting state. When the operation is complete, it will be moved back to ready state.

- Terminated: when all instructions are complete or errors are encountered, process will exit.

Process creation

Mechanism for process creation

- fork: copies the parent PCB into new child PCB. Child continues execution at instruction after fork.

- EXEC: replace child image. Load new program and start from first instruction.

Note:

The parent of all processes: init

What is the role of the CPU scheduler

A CPU scheduler determines which one of the currently ready processes will be dispatched to the CPU to start running, and how long it should run for.

OS must be able to do the following tasks efficiently:

- preempt: interrupt and save current context

- schedule: run scheduler to choose next process

- dispatch: dispatch process and switch into its context

How long should a process run for/ How frequently should we run the scheduler

Longer the process runs means less often we are invoking the task scheduler. Consider the following case:

- running process for amount of time $T_p$

- schedular takes amount of $T_\text{sched}$

$$\text{Useful CPU Work} = \frac{\text{Total Processing Time}}{\text{Total time}} = \frac{T_p}{T_p + T_\text{sched}}$$

Can Processes Interact

An operating system must provide mechanisms to allow processes to interact with each other. Many applications we see today are structured as multiple processes.

Inter Process Communication (IPC) mechanisms:

- transfer data/info between address spaces

- maintain protection and isolation

- provide flexibility and performance

Message-passing IPC

- OS provides communication channel, like shared buffer

- Processes write/read messages to.from channel

- + OS manages

- - overheads: everything needs to go through the OS

Shared memory IPC

- OS establishes a shared channel and maps it into each process address space

- Processes directly read/write from this memory

- +: OS is out of the way

- -: No shared and well defined API because OS is not involved. Can be more error-prone, and developers may need to re-implement code. Mapping memory between processes can also be expensive.

Threads and Concurrency

Toy shop worker metaphor

A worker in a toy shop:

- is an active entity: executing unit of toy order

- works simultaneously with others: many workers completing toy orders

- requires coordination: sharing of tools, parts, workstations

A thread:

- is an active entity: executing unit of a process

- works simultaneously with others: many threads executing

- requires coordination: sharing of I/O devices, CPUs, memory

Process vs Thread

Threads are part of the same virtual address space. Each thread will have a separate program counter, registers, and stack pointer.

Why are threads useful

- Each thread can execute the same code but for different portions of the input. Parallelization helps to speed up processes.

- Threads can execute different parts of the program.

- Specialization with multiple cores: hotter cache.

- Efficiency: lower memory requirement and cheaper IPC.

Are threads useful on a single CPU (or # of threads > # of CPUs)

- If $t_\text{idle} > 2 t_\text{context switch}$, then context switch to hide idling time.

- When switching between threads, it is not necessary to recreate virtual to physical memory maps (the most costly step). Therefore, $t_\text{thread context switch} << t_\text{process context switch}$.

- Multithreading is specially useful to high latency in IO operations.

Benefits to applications and OS code

Multithreaded OS kernel

- threads working on behalf of apps

- OS-level services like daemons or device drivers

What do we need to support threads?

- thread data structure: identify threads, keep track of resource usage

- mechanisms to create and manage threads

- mechanisms to safely coordinate among threads running concurrently in the same address space

Threads and concurrency

Processes: Operating in own address spaces. Opearting system prevents overwriting physical addresses.

Threads: They both use the same virtual and physical addresses. Multiple threads can attempt to access the same data at the same time.

Concurrency Control and Coordination

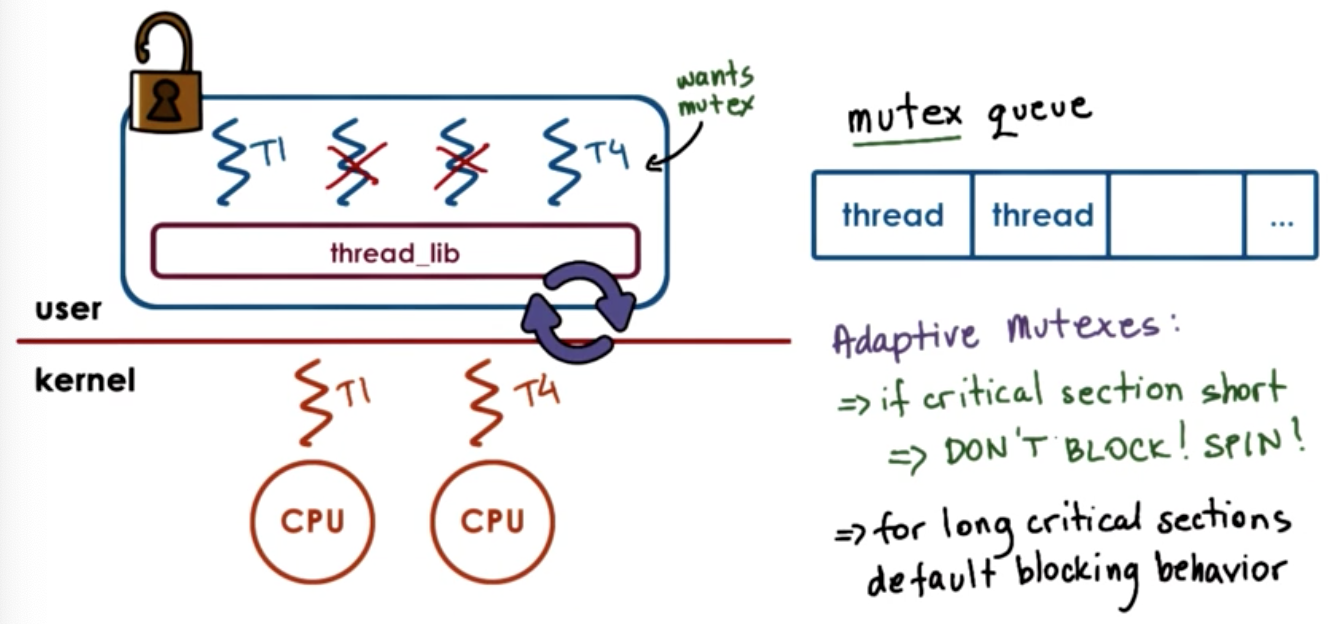

Synchronization Mechanisms

- Mutual Exclusion

- exclusive access to only one thread at a time

- mutex

- Waiting on other threads

- specific condition before proceeding

- condition variable

- Waking up other threads from wait state.

Threads and Thread Creation

- Thread type: thread data structure (threadId, PC, SP, registers, stack, attributes)

Fork(proc, args): create a thread, not UNIX fork.t1 = fork(proc, args)creates a new thread.Join(thread): terminate a thread.

Thread Creation Example

Thread thread1;

Shared_list list;

thread1 = fork(safe_insert, 4);

safe_insert(6);

join(thread1); // Optional, blocks parent threadResult can be:

- 4 $\rightarrow$ 6 $\rightarrow$ NIL

- 6 $\rightarrow$ 4 $\rightarrow$ NIL

How is the list updated?

create new list element e

set e.value = X

read list and list.p_next

set e.point = list.p_next

set list.p_next = eMutual Exclusion

Mutex data structure:

- whether it’s locked

- owner of mutex

- blocked threads

Birrell’s Lock API

lock(m) {

// critical section

} // unlock;Common Thread API

lock(m);

// critical section

unlock(m);Making safe_insert safe

list<int> my_list;

Mutex m;

void safe_insert(int i) {

lock(m) {

my_list.insert(i);

} // unlock;

}Producer/Consumer Example

What if the processing you wish to perform with mutual exclusion needs to occur only under certain conditions?

//main

for i=0..10

producers[i] = fork(safe_insert, NULL) //create producers

consumer = fork(print_and_clear, my_list) //create consumer

// producers: safe_insert

lock(m) {

list->insert(my_thread_id)

} // unlock;

// consumer: print_and_clear

lock(m) {

if my_list.full -> print; clear up to limit of elements of list (WASTEFUL!)

else -> release lock and try again later

} // unlock;Condition Variable

// consumer: print and clear

lock(m) {

while (my_list.not_full()) Wait(m, list_full);

my_list.print_and_remove_all();

}

// producers: safe_insert

lock(m) {

my_list.insert(my_thread_id);

if my_list.full()

Signal(list_full)

}

Condition Variable API

- Wait(mutex, cond): mutex is automatically released and re-acquired on wait

- Signal(cond): notify only one thread waiting on condition

- Broadcast(cond): notify all waiting threads

Reader/Writer Problem

Readers: 0 or more can access

Writer: 0 or 1 can access

if read_counter == 0 and write_counter == 0:

read okay, write okay

if read_counter > 0:

read okay

if write_counter > 0:

read no, write noState of shared file/resource:

- free: resource.counter = 0

- reading: resource.counter > 0

- writing: resource.counter = -1

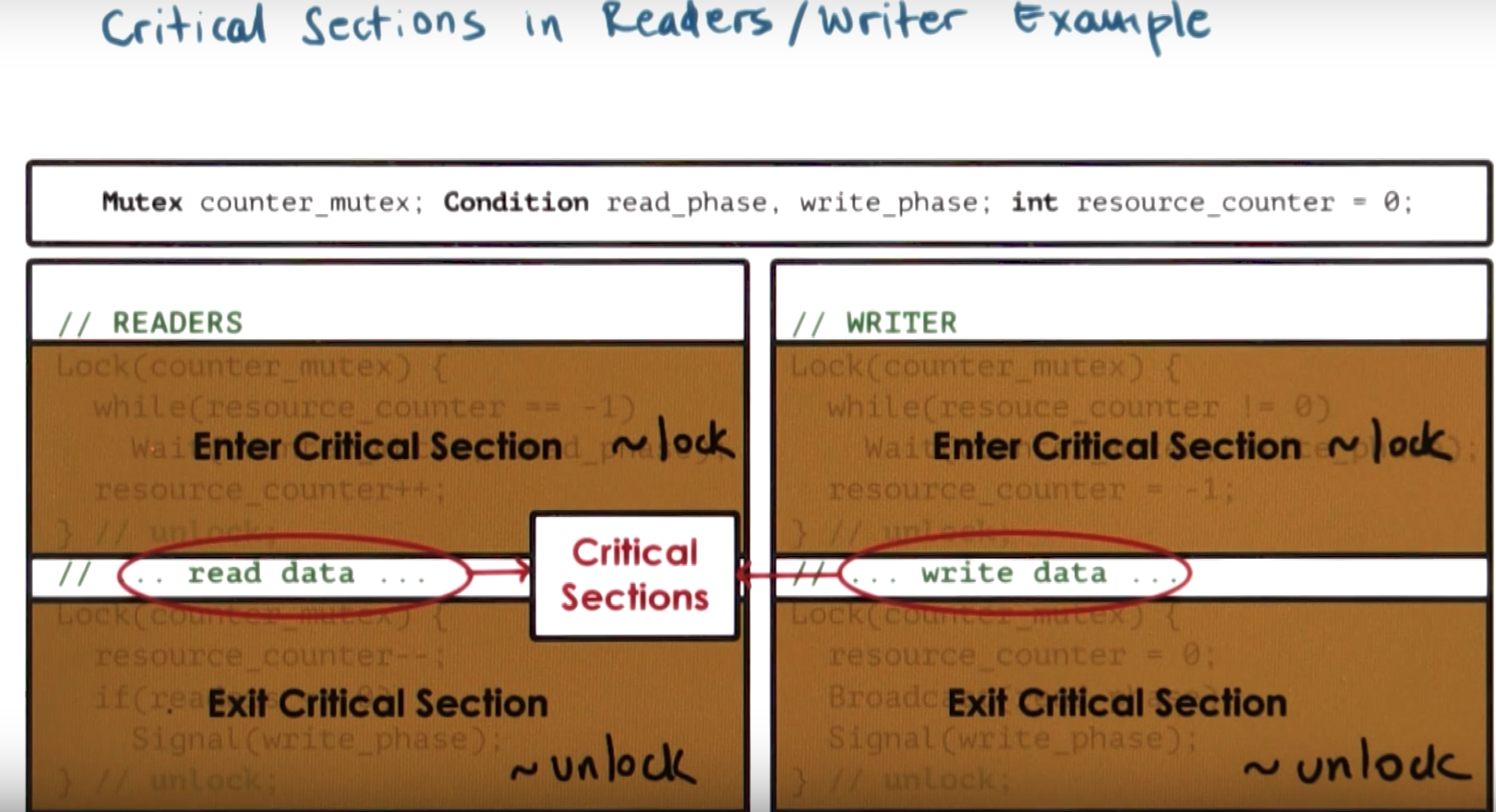

Reader/Writer Example

Mutex counter_mutex;

Condition read_phase, write_phase;

int resource_counter = 0;READERS

Lock(counter_mutex) {

while (resource_counter == -1)

Wait(counter_mutex, read_phase);

resource_counter++;

} // unlock;

// ... read data ...

Lock(counter_mutex) {

resource_counter--;

if (resource_counter == 0)

Signal(write_phase)

} // unlock;WRITER

Lock(counter_mutex) {

while (resource_counter != 0)

Wait(counter_mutex, write_phase);

resource_counter = -1;

} // unlock;

// ... write data ...

Lock(counter_mutex) {

resource_counter = 0;

Broadcast(read_phase);

Broadcast(write_phase);

}Critical Sections in Readers/Writer Example

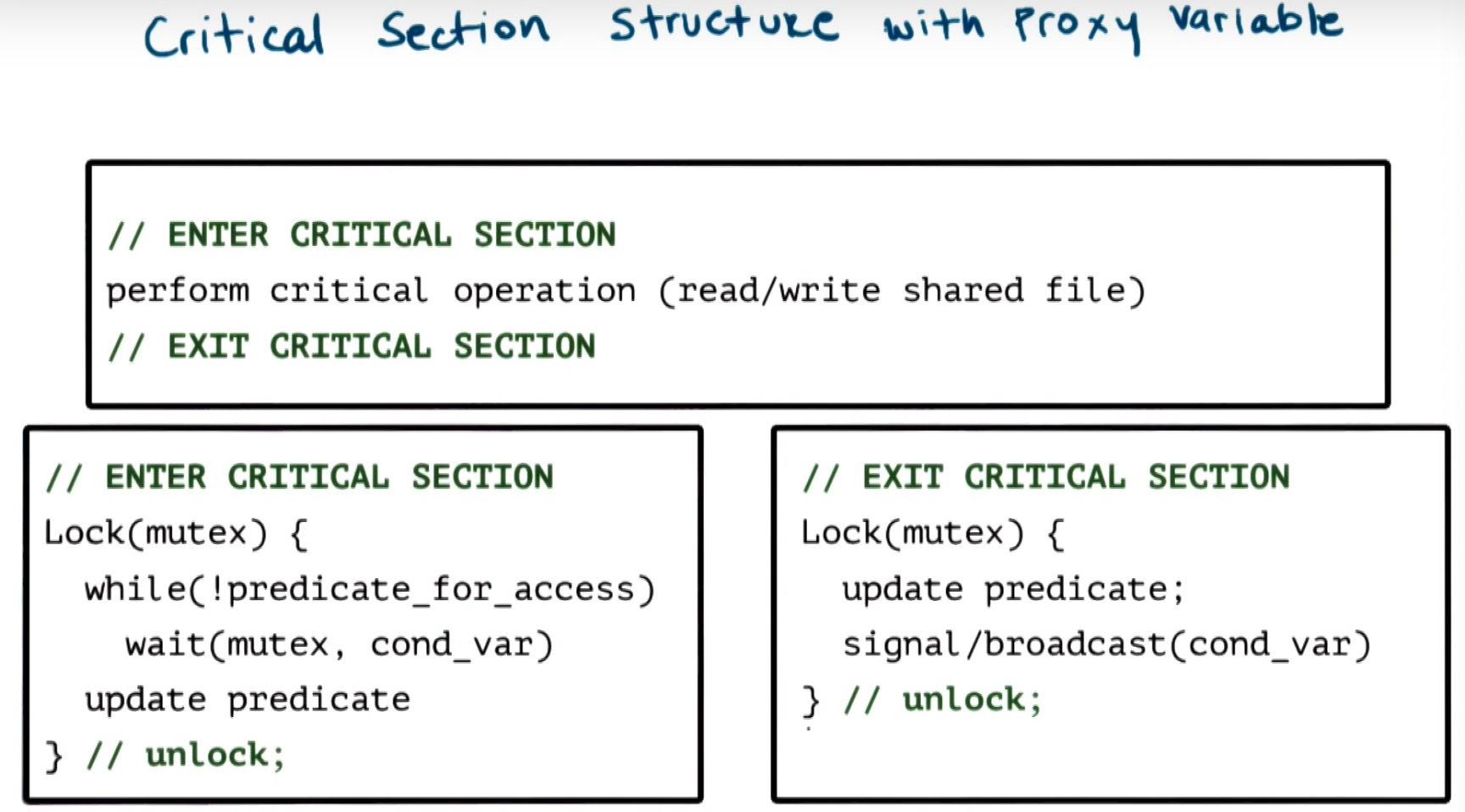

Critical Section Structure with Proxy Variable

Avoiding Common Mistakes

- Keep track of mutex/conditional variables used with a resource

- e.g. mutex_type m1; //mutex for file 1

- Check that you are always (and correctly) using lock and unlock

- e.g. did you forget to lock/unlock? What about compilers?

- Use a single mutex to access a single resource!

- e.g. read and write of the same file has 2 mutexs

- Check that you are signaling correct condition

- Check that you are not using signal when broadcast is needed

- signal: only 1 thread will proceed… remaining threads will continue to wait… possibly indefinitely!

- Ask yourself: do you need priority guarantees?

- thread execution order not controlled by signals to condition variables!

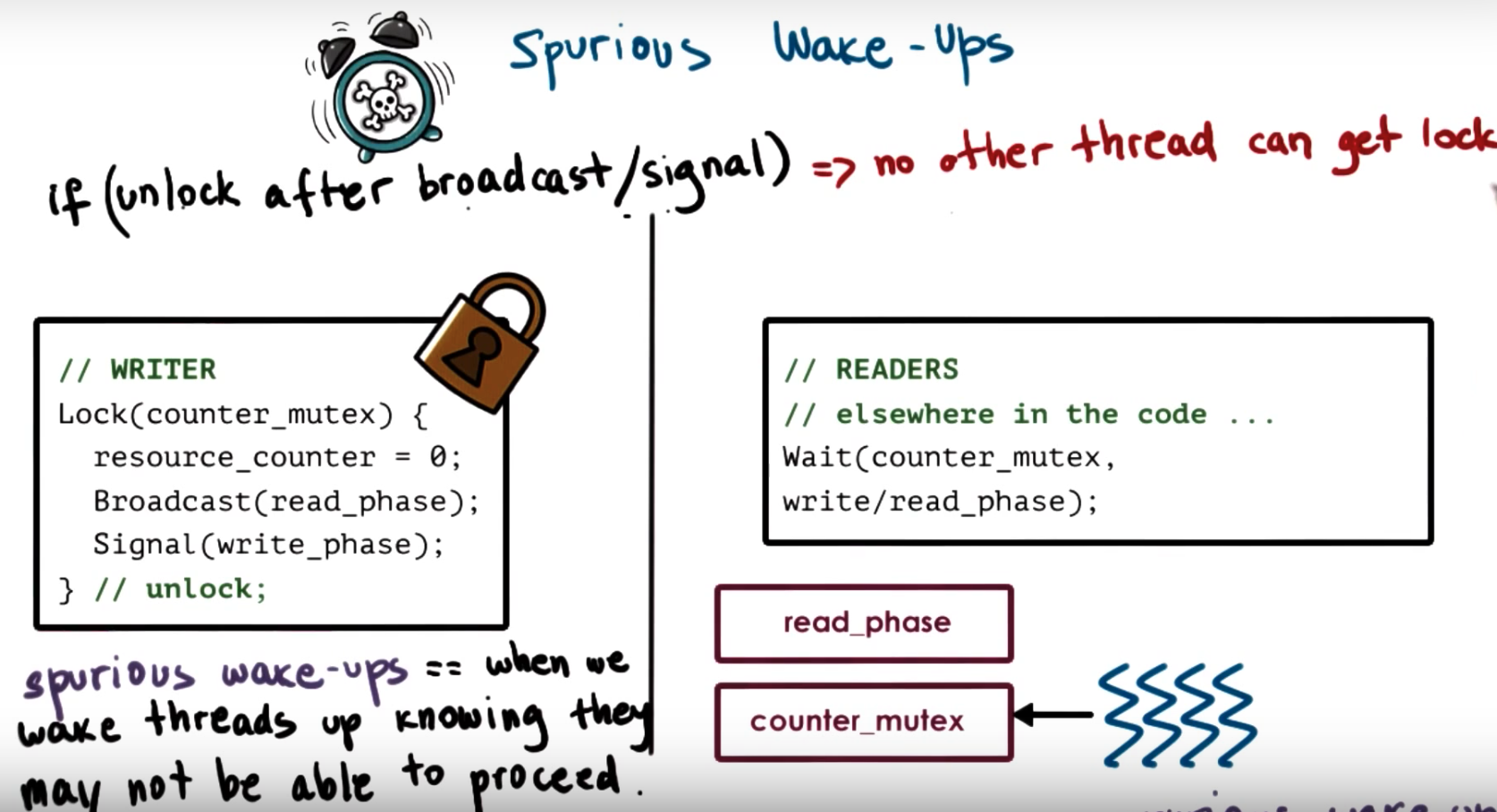

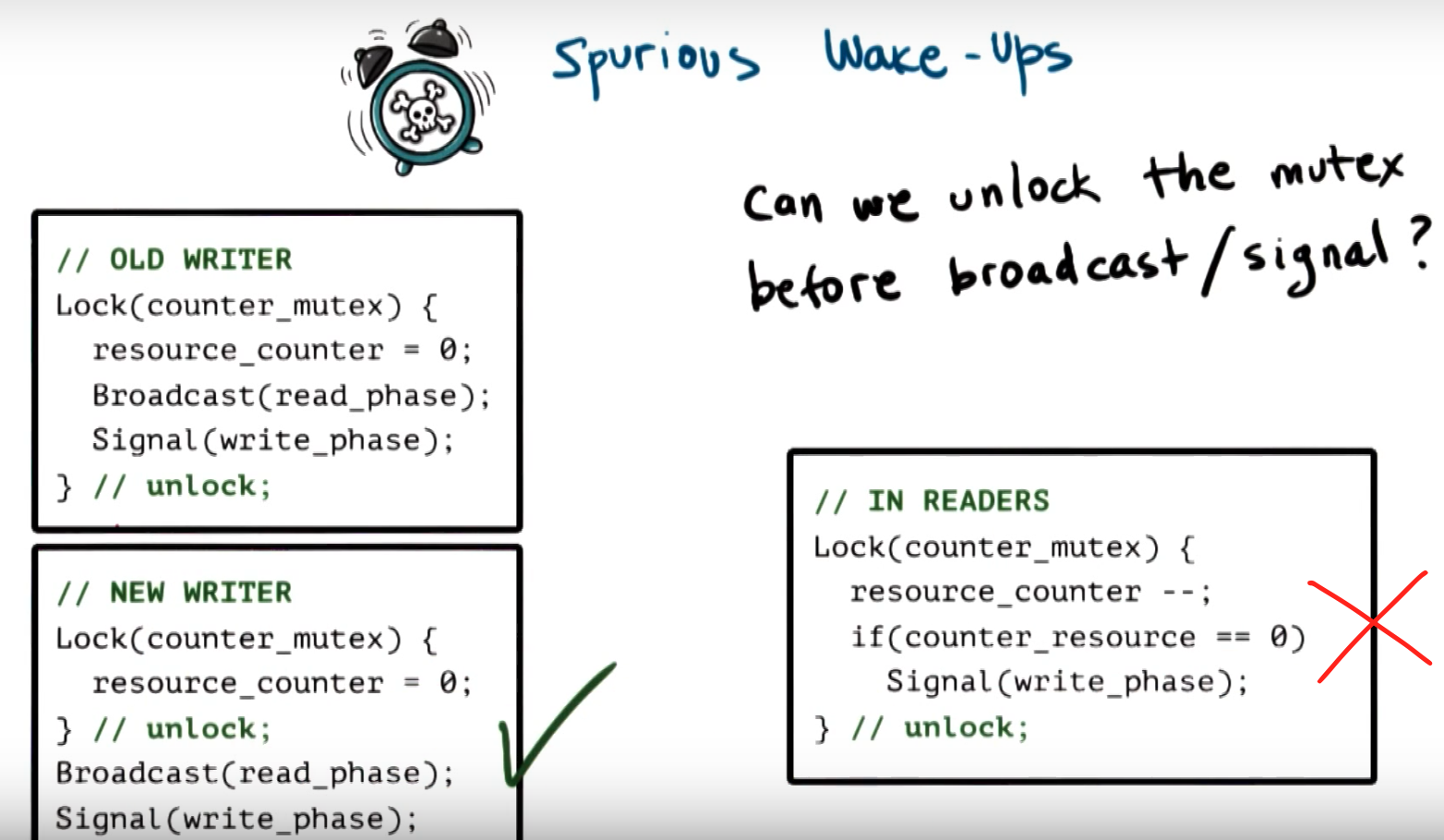

Spurious Wake Ups

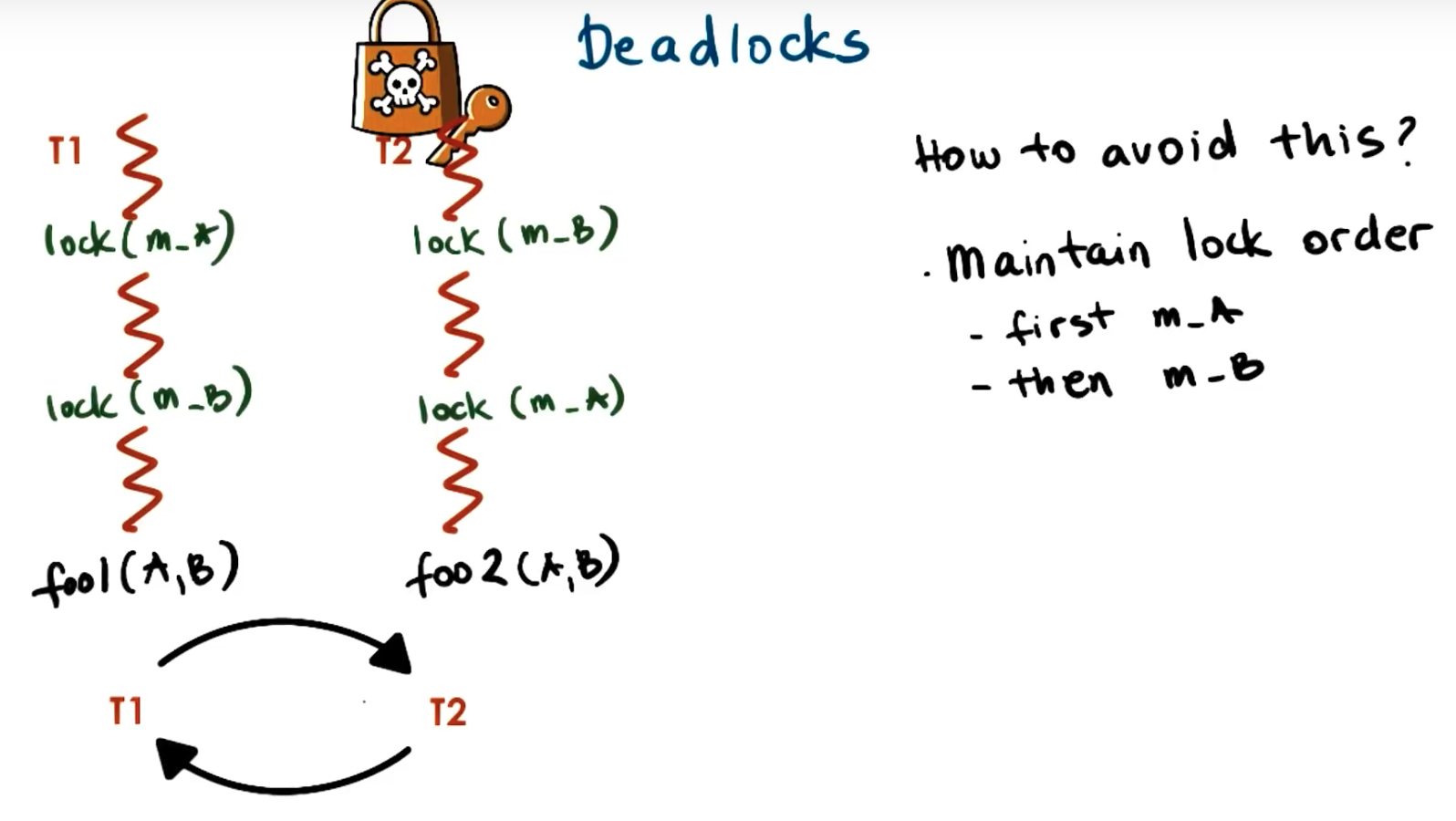

Deadlocks

Definition:

Two or more competing threads are waiting on each other to complete, but none of them ever do.

To avoid deadlocks: Maintain lock order across threads, so there is no dead cycles.

In summary:

A cycle in the wait graph is necessary and sufficient for a deadlock to occur. (edges from thread waiting on a resource to thread owning a resource)

What can we do about it?

- Deadlock prevention (EXPENSIVE)

- Deadlock detection & recovery (ROLLBACK)

- Apply the ostrich Algorithm (DO NOTHING!) => if all else fails… just REBOOT

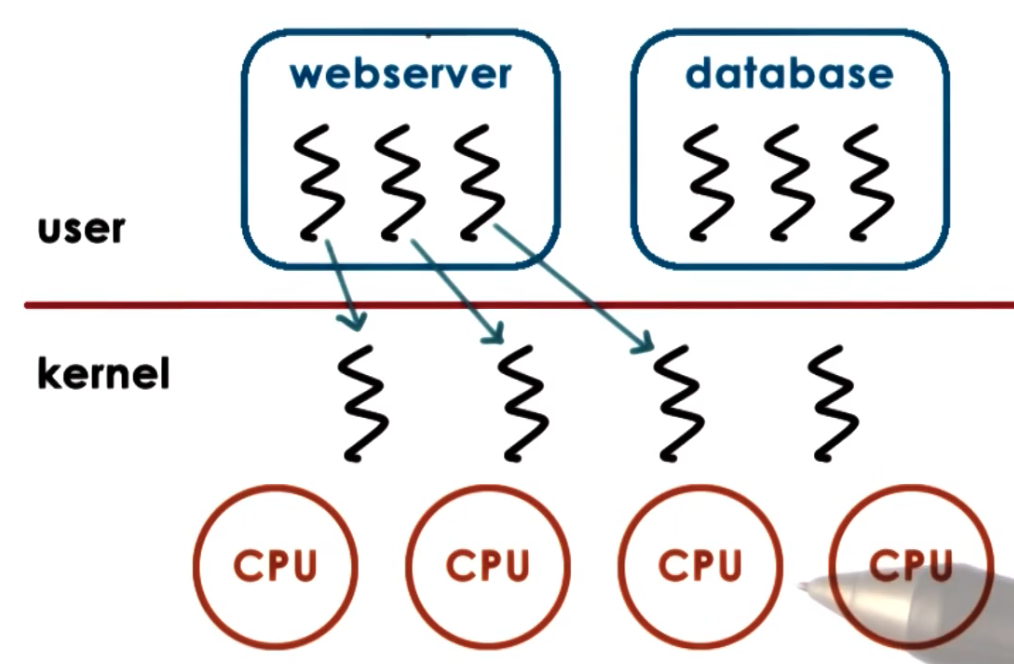

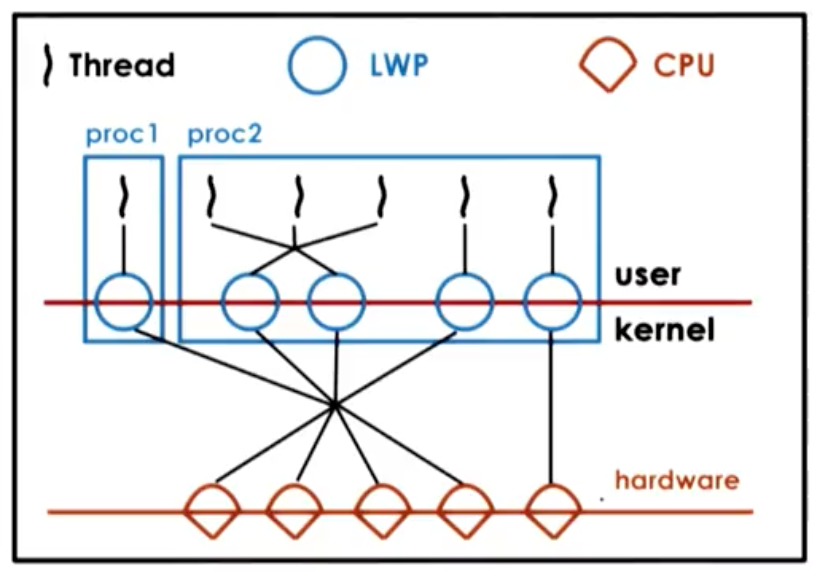

Kernel vs User-Level Threads

One to One Model

- + OS sees/understands threads, synchronization, blocking

- -

- Must go to OS for all operations (may be expensive)

- OS may have limits on policies, thread #

- portability

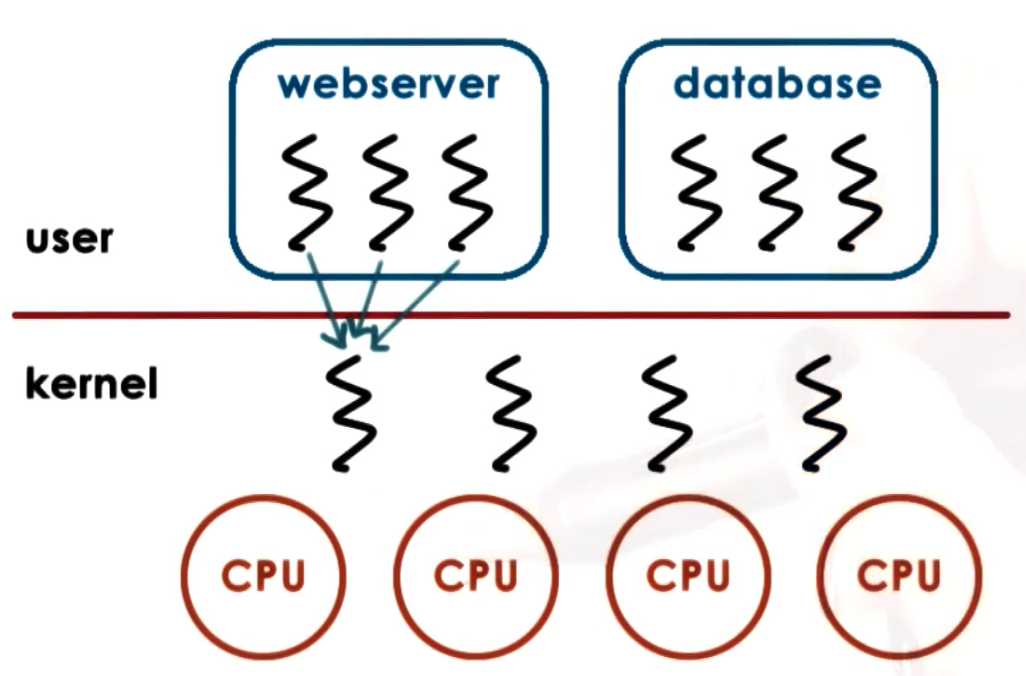

Many to One model

- + totally portable, doesn’t depend on OS limits and policies

- -

- OS has no insights into application needs

- OS may block entire process if one user-level thread blocks on I/O

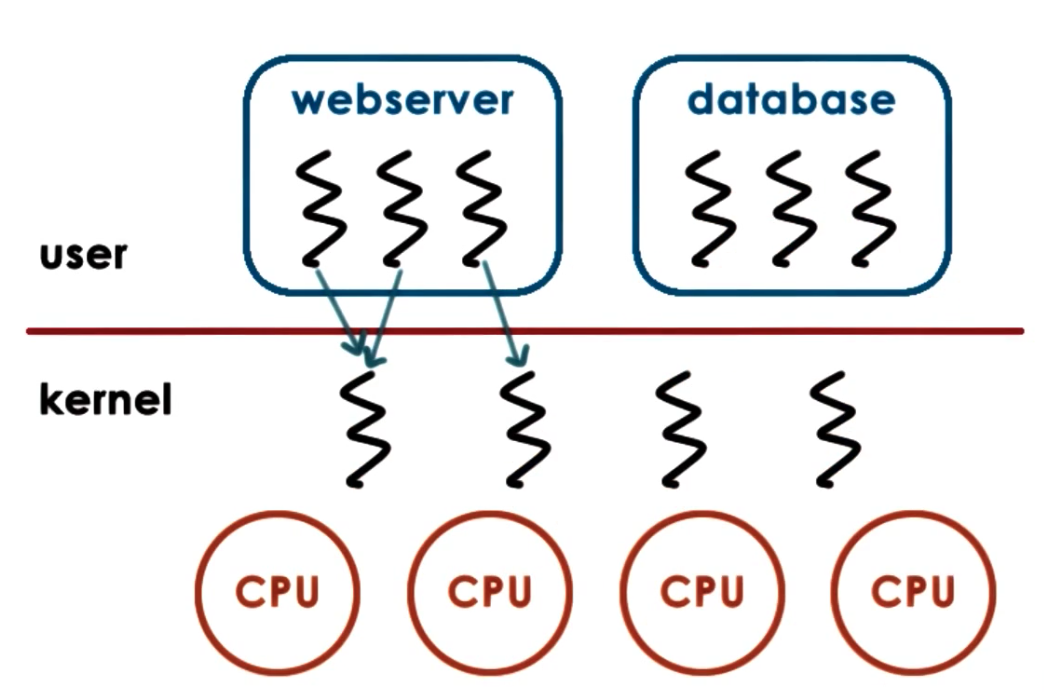

Many to Many Model

- +

- can be best of both worlds

- can have bound or unbound threads

- -

- requires coordination between user and kernel level thread managers

Scope

- System Scope: System-wide thread management by OS-level thread managers (e.g. CPU scheduler)

- Process Scope: User-level library manages threads within a single process

Multithreading Patterns

Toy shop example: for each wooden toy order, we:

- accept the order

- parse the order

- cut wooden parts

- paint and add decorations

- assemble the wooden toys

- ship the order

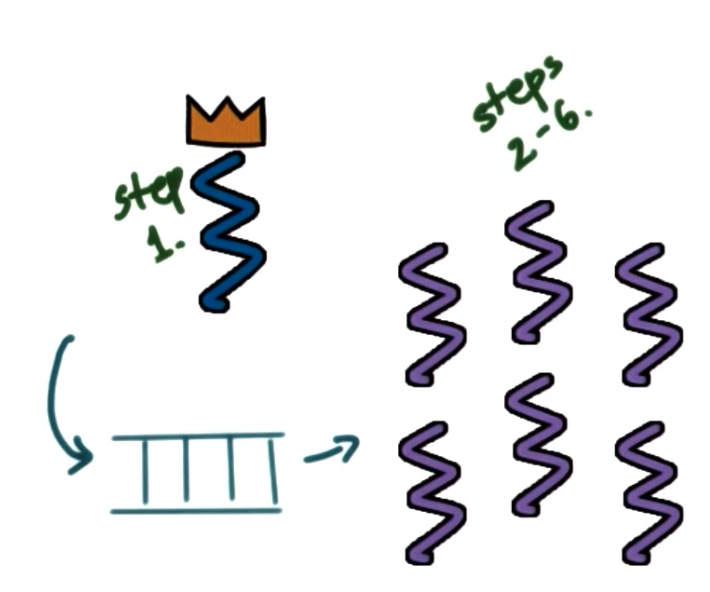

Boss/Workers Pattern

Boss-Workers:

- boss: assigns work to workers (step 1)

- workers: performs entire task (step 2-6)

Throughput of the system limited by boss thread => must keep boss efficient

$$\text{Throughput} = \frac{1}{\text{boss time per order}}$$

Boss assigns work by

- directly signalling specific worker

- + workders don’t need to synchronize

- - boss must track what each worker is doing, and throughput will go down

- placing work in producer/consumer queue (more often used)

- + boss doesn’t need to know details about workers

- - queue synchronization: workers need to synchronize access to the queue, etc

How many workers

- on demand

- pool of workers

- static or dynamic

Boss-Workers:

- boss: assigns work to workers (step 1)

- workers: performs entire task (step 2-6)

- placing work in producer/consumer queue (more often used)

- pool of workers

- + simplicity

- - thread pool management

- - locality

Boss-Workers Variants:

- all workders created equal vs workers specialized for certain tasks

- + better locality (hotter cache); quality of service management

- - load balancing

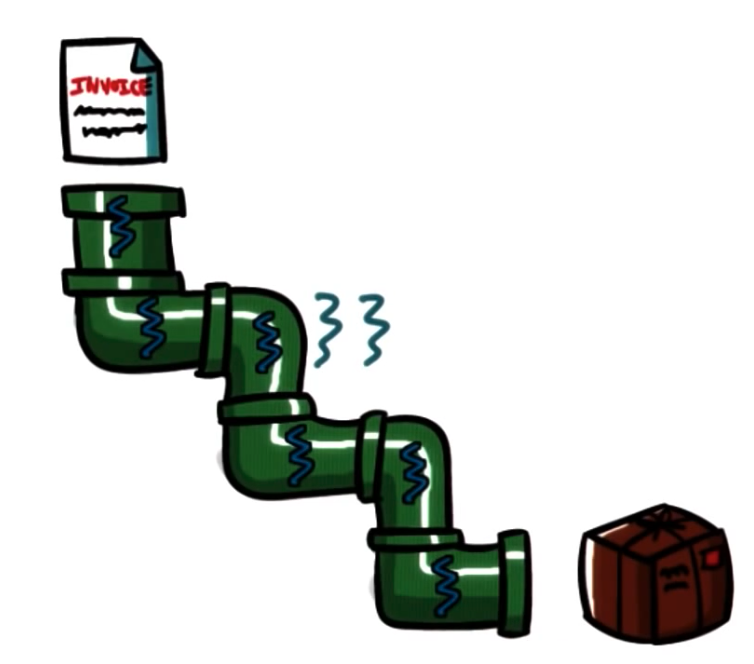

Pipeline Pattern

Pipeline:

- threads assigned one subtask in the system

- entire tasks == pipeline of threads

- multiple tasks concurrently in the system, in different pipeline stages

- throughput == weakest link => pipeline stage == thread pool

- shared-buffer based communication between stages

In summary:

- sequence of stages

- stage == subtask

- each stage == thread pool

- buffer-based communication

- + specialization and locality

- - balancing and synchronization overheads

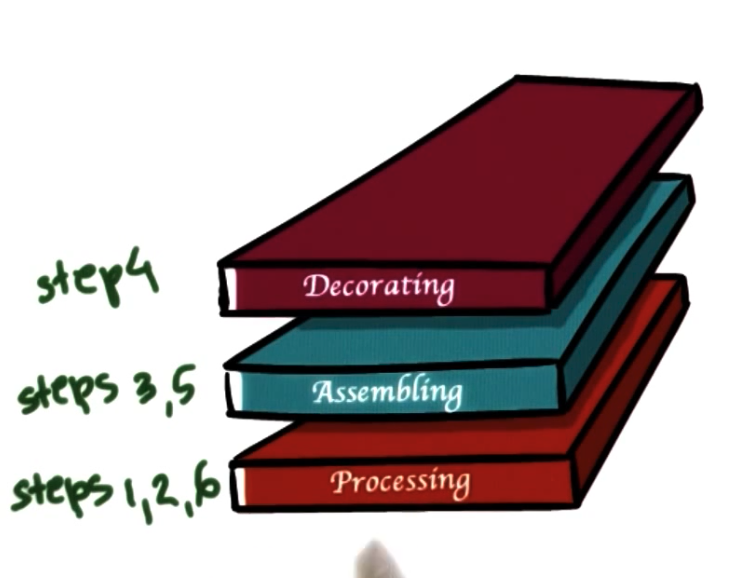

Layered Pattern

Layered:

- each layer group of related subtasks

- end-to-end task must pass up and down through all layers

- + specialization and locality, but less fine-grained than pipeline

- - not suitable for all applications

- - synchronization

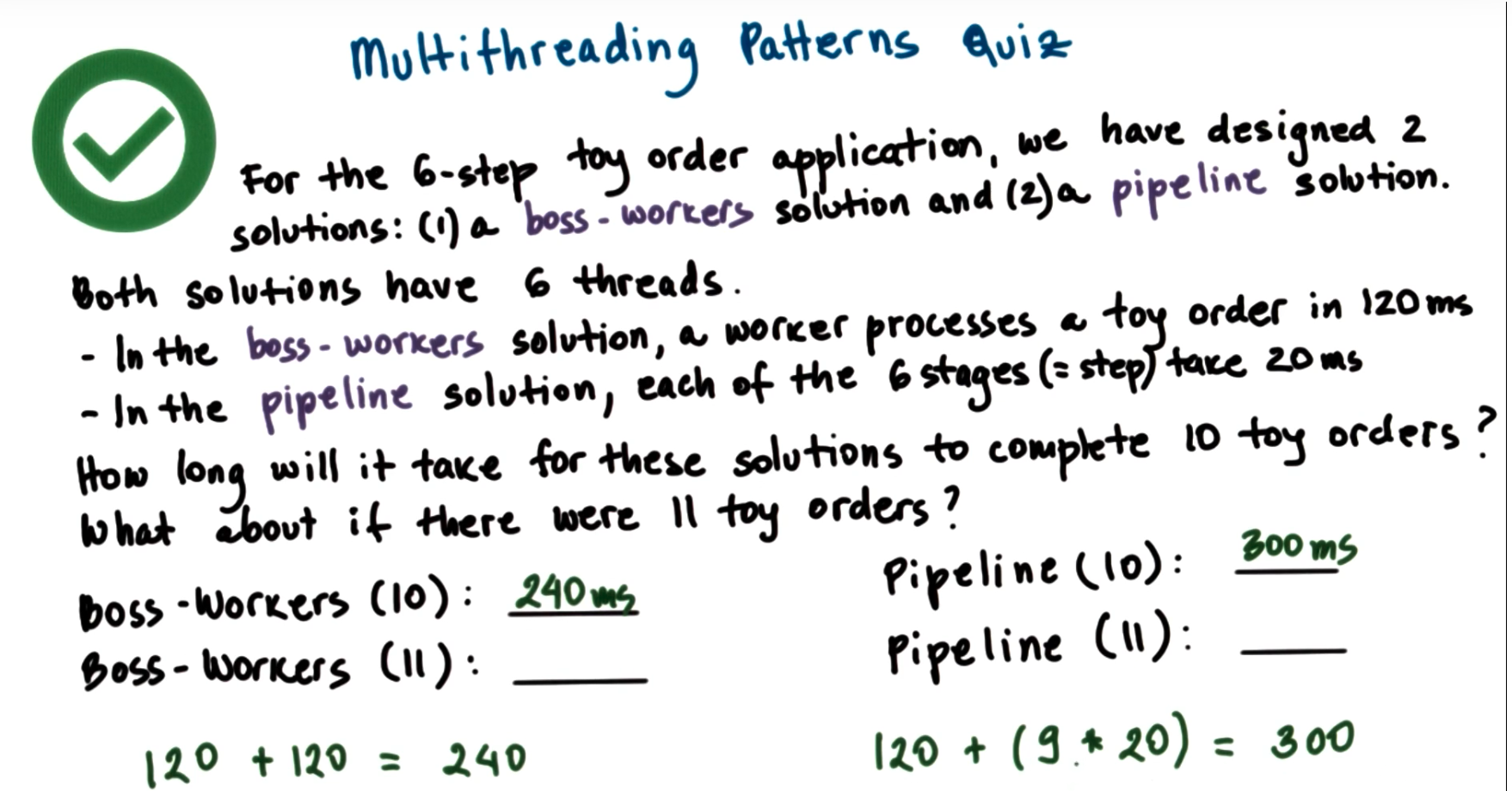

Time to finish orders

Boss-Worker:

$$ \text{Time to Finish 1 Order} \times \text{Ceiling}(\text{num orders}/\text{num threads}) $$

Pipeline:

$$ \text{time to finish first order} + (\text{remaining orders} \times \text{time to finish last stage})$$

Threads Case Study: PThreads

PThreads: POSIX Threads

POSIX: Portable Operating System Interface

Pthread creation

Threadpthread_t aThread; //type of threadFork(proc, args)int pthread_create( pthread_t *thread, const pthread_attr_t *attr, void * (*start_routine)(void *), void *arg );Join(thread)int pthread_join(pthread_t thread, void **status)

Pthread Attributes

pthread_attr_t- specified in

pthread_create - defines features of the new thread

- has default behavior with NULL in

pthread_create

- specified in

attributes

- stack size

- inheritance

- joinable

- scheduling policy

- priority

- system/process scope

methods

int pthread_attr_init(pthread_attr_t *attr); int pthread_attr_destroy(pthread_attr_t *attr); pthread_attr_{set/get}{attribute}

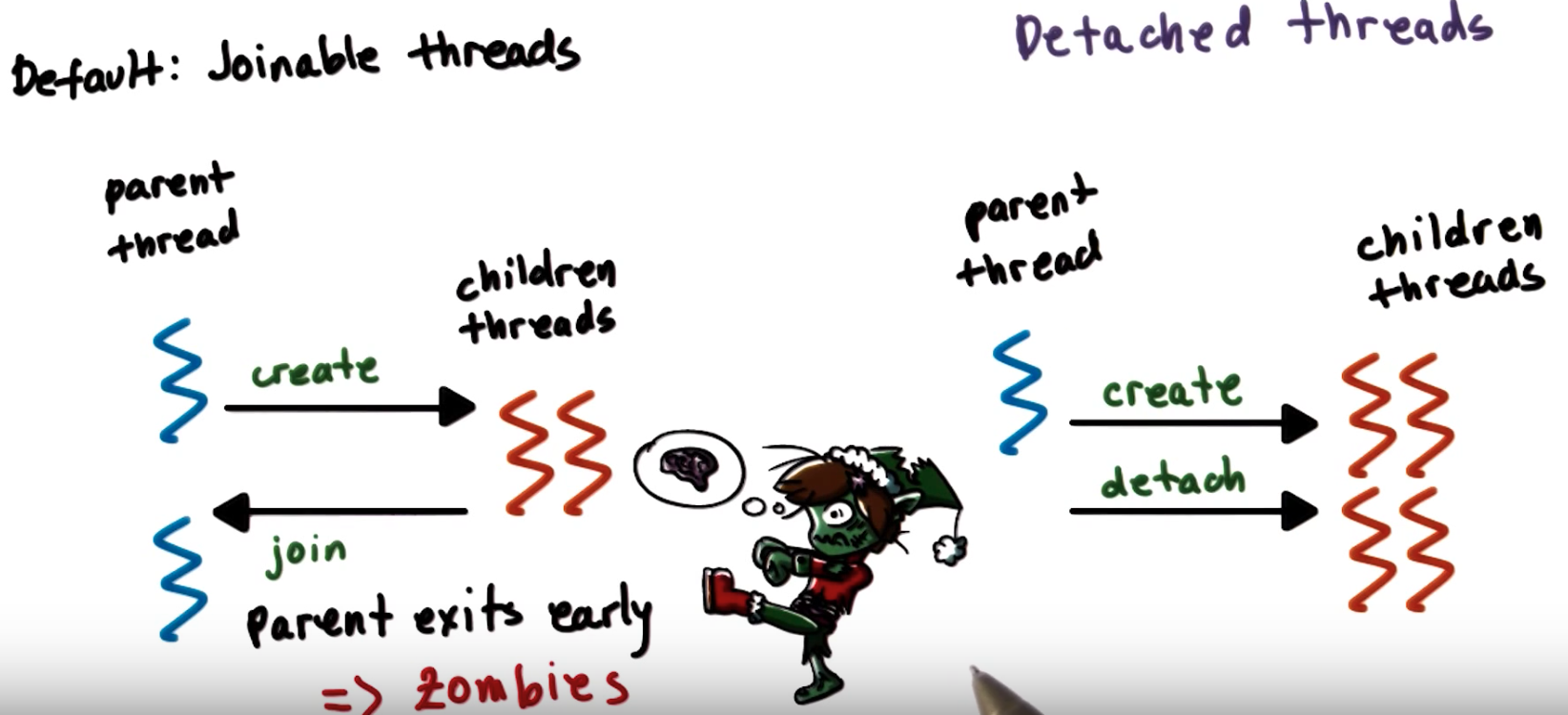

Detaching Pthread

int pthread_detach();Example

#include <stdio.h>

# include <pthread.h>

void *foo (void *arg) { /* thread main */

printf("Foobar!\n");

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

int main (void) {

int i;

pthread_t tid;

pthread_attr_t attr;

pthread_attr_init(&attr); // required!

pthread_attr_setdetachstate(&attr, PTHREAD_CREATE_DETACHED);

pthread_attr_setscope(&attr, PTHREAD_SCOPE_SYSTEM); // share resource with all other threads in the system

pthread_create(&tid, &attr, foo, NULL);

return 0;

}Compiling Pthreads

#include <pthread.h>in main file- compile source with

-lpthreador-pthreadgcc -o main main.c -lpthread gcc -o main main.c -pthread - check return values of common functions

Quiz 1

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

void *hello (void *arg) { /* thread main */

printf("Hello Thread\n");

return 0;

}

int main (void) {

int i;

pthread_t tid[NUM_THREADS];

for (i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* create/fork threads */

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, hello, NULL);

}

for (i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* wait/join threads */

pthread_join(tid[i], NULL);

}

return 0;

}Quiz 2

/* A Slightly Less Simple PThreads Example */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

void *threadFunc(void *pArg) { /* thread main */

int *p = (int*)pArg;

int myNum = *p;

printf("Thread number %d\n", myNum);

return 0;

}

int main(void) {

int i;

pthread_t tid[NUM_THREADS];

for(i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* create/fork threads */

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, threadFunc, &i);

}

for(i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* wait/join threads */

pthread_join(tid[i], NULL);

}

return 0;

}iis defined in main => it’s globally visible variable- when it changes in one thread => all other threads see new value

Quiz 3

/* PThread Creation Quiz 3 */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define NUM_THREADS 4

void *threadFunc(void *pArg) { /* thread main */

int myNum = *((int*)pArg);

printf("Thread number %d\n", myNum);

return 0;

}

int main(void) {

int i;

int tNum[NUM_THREADS];

pthread_t tid[NUM_THREADS];

for(i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* create/fork threads */

tNum[i] = i;

pthread_create(&tid[i], NULL, threadFunc, &tNum[i]);

}

for(i = 0; i < NUM_THREADS; i++) { /* wait/join threads */

pthread_join(tid[i], NULL);

}

return 0;

}Pthread Mutexes

“to solve mutual exclusion problems among concurrent threads”

mutexpthread_mutext_t aMutex; // mutex typeLock(mutex)// explicit lock int pthread_mutex_lock(pthread_mutex_t *mutex); // run critical section // explicit unlock int pthread_mutex_unlock(pthread_mutex_t *mutex);

safe insert example

list<int> my_list;

pthread_mutex_t m;

void safe_insert(int i) {

pthread_mutex_lock(m);

my_list.insert(i);

pthread_mutex_unlock(m);

}Other Mutex Operations

Attributes

int pthread_mutex_init(pthread_mutex_t *mutex, const pthread_mutexattr_t *attr);

// mutex attributes == specifies mutex behavior when a mutex is shared among processesTry Lock

int pthread_mutex_trylock(pthread_mutex_t *mutex);Destroy

int pthread_mutex_destroy(pthread_mutex_t *mutex);Mutex Safety Tips

- Shared data should always be accessed through a single mutex

- mutex scope must be visible to all

- globally order locks

- for all threads, lock mutexes in order

- always unlock a mutex

- always unlock the correct mutex

Pthread Condition Variables

Conditionpthread_cond_t aCond; // type of cond variableWaitint pthread_cond_wait(pthread_cond_t *cond, pthread_mutex_t *mutex);Signalint pthread_cond_signal(pthread_cond_t *cond);Broadcastint pthread_cond_broadcast(pthread_cond_t *cond);Others

pthread_cond_initpthread_cond_destroy

Condition Variable Safety Tips

- Do not forget to notify waiting threads

- predicate change => signal/broadcast correct condition variable

- When in doubt broadcast

- but performance loss

- You do not need a mutex to signal/broadcast

Producer/Consumer Example

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <pthread.h>

#define BUF_SIZE 3 /* Size of shared buffer */

int buffer[BUF_SIZE]; /* shared buffer */

int add = 0; /* place to add next element */

int rem = 0; /* place to remove next element */

int num = 0; /* number elements in buffer */

pthread_mutex_t m = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER; /* mutex lock for buffer */

pthread_cond_t c_cons = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER; /* consumer waits on this cond var */

pthread_cond_t c_prod = PTHREAD_COND_INITIALIZER; /* producer waits on this cond var */

void *producer (void *param);

void *consumer (void *param);

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

pthread_t tid1, tid2; /* thread identifiers */

int i;

/* create the threads; may be any number, in general */

if(pthread_create(&tid1, NULL, producer, NULL) != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Unable to create producer thread\n");

exit(1);

}

if(pthread_create(&tid2, NULL, consumer, NULL) != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "Unable to create consumer thread\n");

exit(1);

}

/* wait for created thread to exit */

pthread_join(tid1, NULL);

pthread_join(tid2, NULL);

printf("Parent quiting\n");

return 0;

}

/* Produce value(s) */

void *producer(void *param) {

int i;

for (i=1; i<=20; i++) {

/* Insert into buffer */

pthread_mutex_lock (&m);

if (num > BUF_SIZE) {

exit(1); /* overflow */

}

while (num == BUF_SIZE) { /* block if buffer is full */

pthread_cond_wait (&c_prod, &m);

}

/* if executing here, buffer not full so add element */

buffer[add] = i;

add = (add+1) % BUF_SIZE;

num++;

pthread_mutex_unlock (&m);

pthread_cond_signal (&c_cons);

printf ("producer: inserted %d\n", i);

fflush (stdout);

}

printf("producer quiting\n");

fflush(stdout);

return 0;

}

/* Consume value(s); Note the consumer never terminates */

void *consumer(void *param) {

int i;

while(1) {

pthread_mutex_lock (&m);

if (num < 0) {

exit(1);

} /* underflow */

while (num == 0) { /* block if buffer empty */

pthread_cond_wait (&c_cons, &m);

}

/* if executing here, buffer not empty so remove element */

i = buffer[rem];

rem = (rem+1) % BUF_SIZE;

num--;

pthread_mutex_unlock (&m);

pthread_cond_signal (&c_prod);

printf ("Consume value %d\n", i); fflush(stdout);

}

return 0;

}Thread Design Considerations

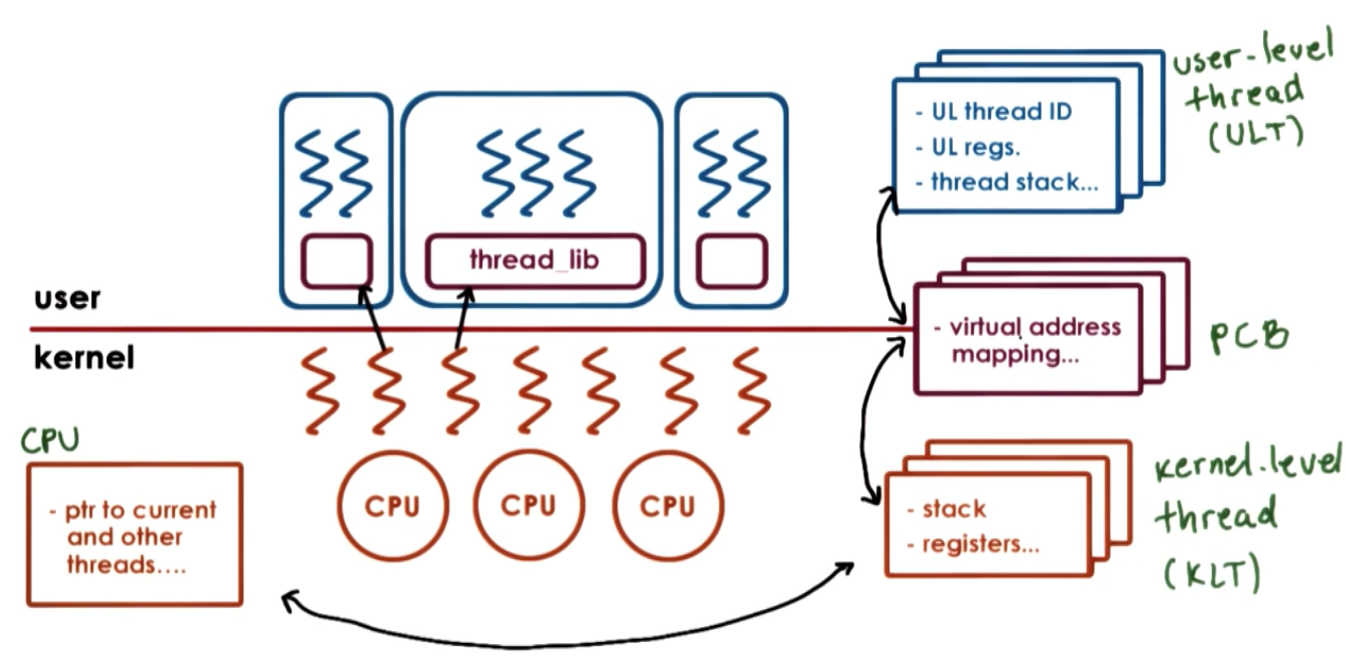

Kernel vs User-level Threads

- Kernel-level Threading: OS Kernel maintains thread abstraction, scheduling, sync, …

- User-level Threading:

- User-level library provides thread abstraction, scheduling, sync

- different process can use different threading libraries

- Mappings: one to one, one to many, many to one

Thread-related data structures

Hard and Light Process State

When two threads point to the same process, there are information in the process control block that are specific to each thread, and there are also information that’s shared between these two threads. We split these information into two states:

- “light” process state: specific to each thread. e.g. signal mask, sys call args

- “hard” process state: shared across threads belong to the same process e.g. virtual address mapping

Rationale for Multiple Data Structures

Single PCB:

- large continuous data structures

- - scalability

- private for each entity

- - overheads

- saved and restored on each context switch

- - performance

- update for any changes

- - flexibility

Multiple data structures:

- smaller data structures

- + scalability

- easier to share

- + overheads

- on context switch only save and restore what needs to change

- + performance

- update for any changes

- user-level library need only update portion of the state

- + flexibility

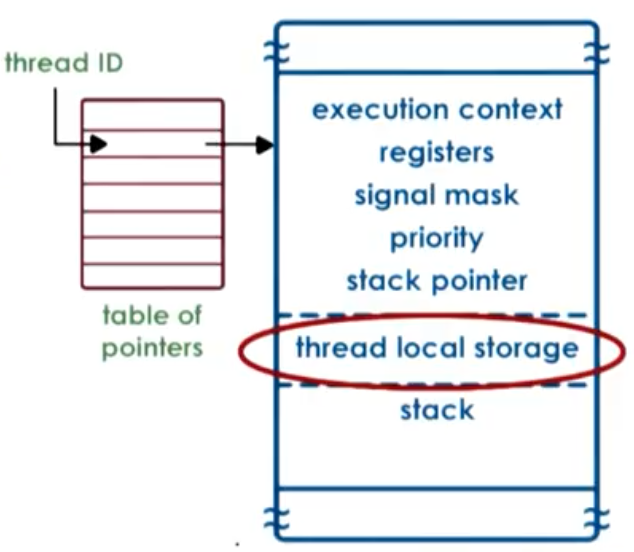

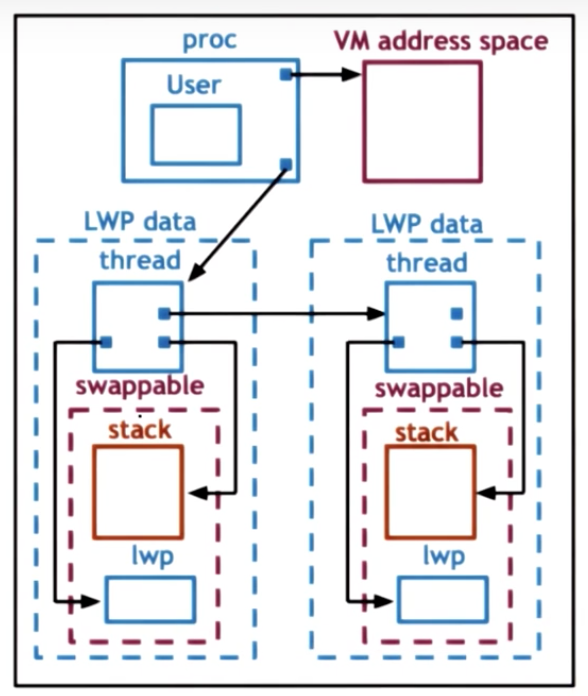

SunOS 5.0 Threading Model

User-level Thread Data Structures

“Implementing Lightweight Threads”

- not POSIX threads, but similar

- thread creation => thread ID (tid)

- tid => index into table of pointers

- table pointers point to per thread data structure

- stack growth can be dangerous! As OS do not have knowledge of multiple threads, as stack of one thread grows, it can overwrite data for another thread. Debug is hard as cause error in one thread is caused by another thread.

- solution => red zone (portion of virtual address space that’s not allocated. When thread grows large, it will write to red zone, which will in turn cause a fault. Now it is easier to reason about the fault because the problem is caused directly by the same source.)

Kernel-level Data Structures

Process

- list of kernel-level threads

- virtual address space

- user credentials

- signal handlers

Light-Weight Process (LWP): similar to ULT, but visible to kernel. Not needed when process is not running

- user level registers

- system call args

- resource usage info

- signal mask

Kernel-level Threads: information needed even when process not running => not swappable

- kernel-level registers

- stack pointer

- scheduling info (class, …)

- pointers to associated LWP process, CPU structures

CPU

- current thread

- list of kernel-level thread

- dispatching and interrupt handling information

Basic Thread Management Interactions

- User-level library does not know what is happening in the kernel

- Kernel does not know what is happening in user-level library

=> System calls and special signals allow kernel and ULT library to interact and coordinate

Also see: pthread_setconcurrency()

Lack of Thread Management Visibility

User-Level library Sees:

- ULTs

- available KLTs

Kernel sees:

- KLTs

- CPUs

- KL scheduler

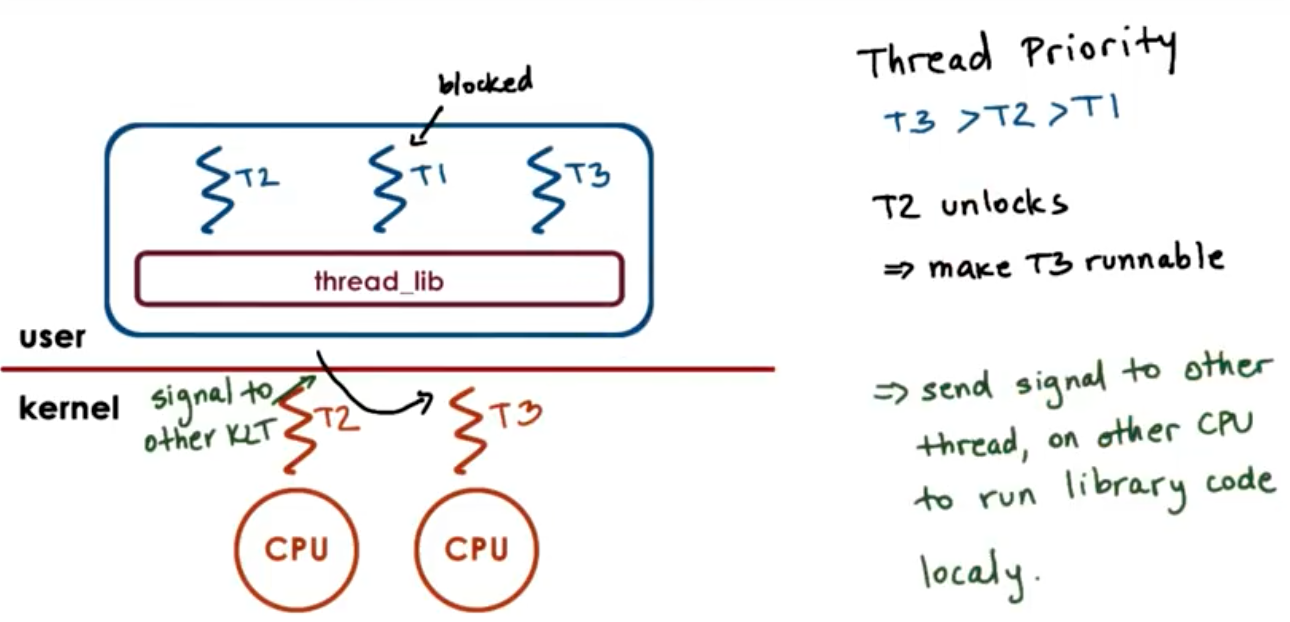

User level thread has a lock => kernel preempted the thread => none of other user level threads can proceed => kernel cycle through threads, and complete the thread with lock

Many to Many:

- UL Scheduling decisions

- change ULT-KLT mapping

Invisible to Kernel:

- mutex variable

- wait queues

Problem: Visibility of state and decisions between kernel and user level library; one to one helps address some of these issues

How/When does the UL library run>

Process jumps to UL library scheduler when:

- ULTs explicitly yield

- timer set by UL library expires

- ULTs call library functions like lock/unlock

- blocked threads become runnable

ULT library scheduler

- runs on ULT operations

- runs on signals from timer or kernel

Issues on multiple CPUs

Synchronization-Related Issues

Destroying Threads

- Instead of destroying… reuse threads

- When a thread exits

- put on a death row

- periodically destroyed by reaper thread

- otherwise thread structures/stacks are reused => performance gains

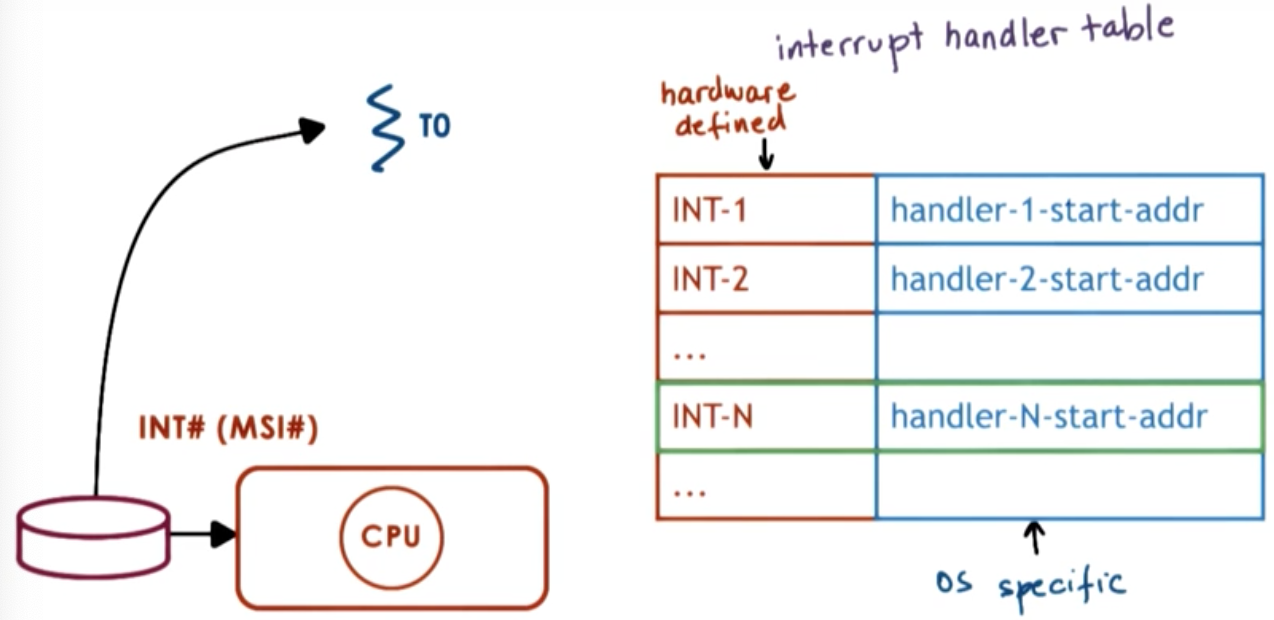

Interrupts vs Signals

Interrupts

- events generated externally by components other than the CPU (I/O devices, timers, other CPUs)

- determined based on the physical platform

- appear asynchronously

- external notification to notify CPU some event has occurred

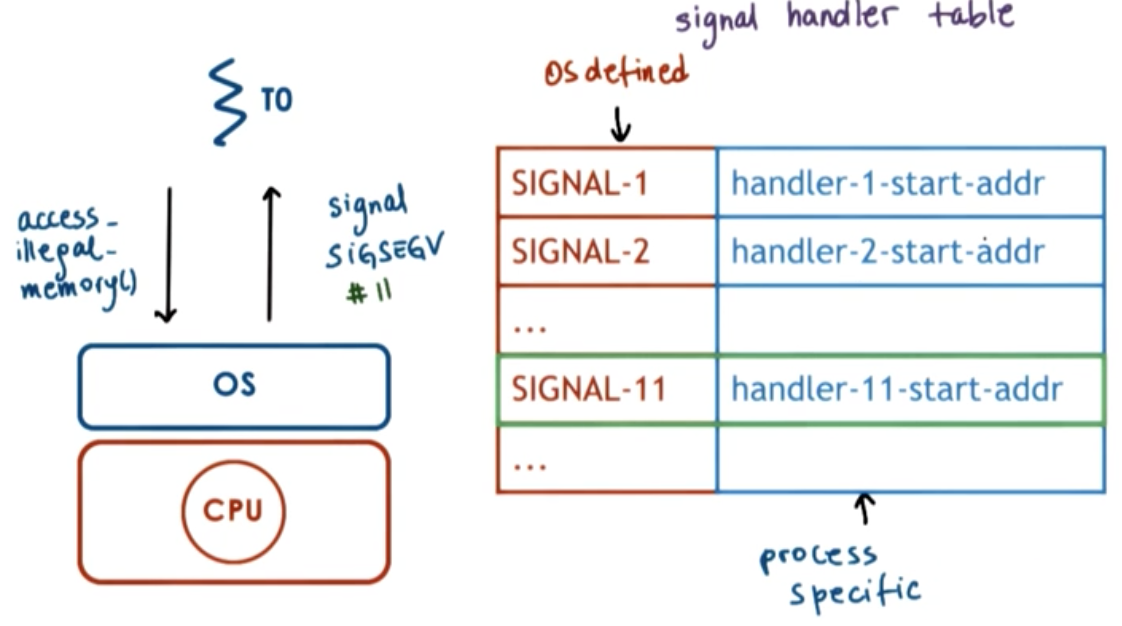

Signals

- events triggered by the CPU and software running on it

- determined based on the operating system

- appear synchronously or asynchronously

Interrupts and signals

- have a unique ID depending on the hardware or OS

- can be masked and disabled/suspended via corresponding mask

- per-CPU interrupt mask, per-process signal mask

- If enabled, trigger corresponding handler

- interrupt handler set for entire system by OS

- signal handlers set on per process basis, by process

Visual Metaphor

Toyshop example:

- hanlded in specific ways

- safety protocols, hazard plans

- can be ignored

- continue working

- expected or unexpected

- happen regularly or irregularly

Interrupt and signal:

- hanlded in specific ways

- interrupt and signal handlers

- can be ignored

- interrupt/signal mask

- expected or unexpected

- appear synchronously or asynchronously

Interrupts

MSI: message signal interruptor

Signals

Handlers/Actions

- Default Actions

- Terminate, Ignore, Terminate and Core Dump, Stop or Continue

- Process Installs Handler

- signal(), sigaction()

- for most signals, some cannot be caught

Synchronous Signals

- SIGSEGV (access to protected memory)

- SIGFPE (divide by zero)

- SIGKILL (kill, id) can be directed to a specific thread

Asynchronous Signals

- SIGKILL (kill)

- SIGALARM

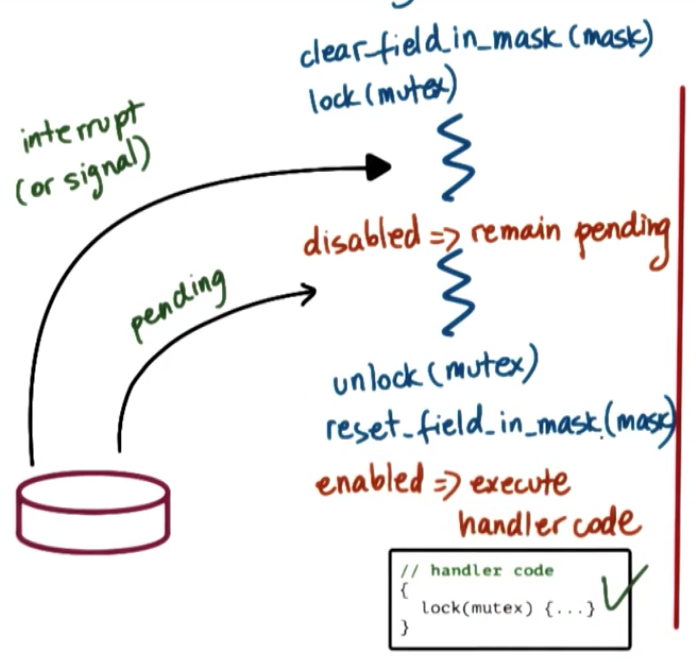

Why disable interrupts or signals?

Sometimes interrupts/signals can create deadlocks.

- keep handler code simple => too restrictive

- control interruptions by handler code => use interrupt/signal masks

- mask is a sequences of 0s and 1s, e.g.

0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 ...: 0 - disabled, 1 - enabled

- mask is a sequences of 0s and 1s, e.g.

More on masks

Interrupt masks are per CPU:

- if mask diables interrupt => hardware intterupt routing mechanism will not deliver interrupt to CPU

Signal masks are per execution context (ULT on top of KLT):

- if masks disables signal => kernel sees mask and will not interrupt corresponding thread

Interrupts on Multicore Systems

- Interrupts can be directed to any CPU that has them enabled

- may set interrupt on just a single core => avoids overheads and perturbations on all other cores

Types of signals

One-shot signals

- “n signals pending == 1 signal pending”: signal will be handled at least once

- must be explicitly re-enabled; e.g. the handler has been invoked by signal. Future instances of the signal will be handled by OS default, or ignored.

Real Time Signals

- “if n signals raised, then handler is called n times”

POSIX signals

SIGINTterminal interrupt signalSIGURGhigh bandwidth data is available on a socketSIGTTOUbackground process attempting writeSIGXFSZfile size limit exceeded